The Urban Patch began by exploring the history of inner cities and asking questions about their future.

The following text and images are excerpts from the Past Forward research paper that was presented in 2011 at the Lean Years Conference at the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan, the 2011 American Community Gardening Association Conference, and the 2012 Parks for the People Symposium sponsored by the Pratt Institute, Van Alen Institute & National Park Service. Images are courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society.

1.

Today’s focus on the development of “sustainable” communities as being critical to the recovery of the economy raises important questions: What is sustainable environmentally, economically, and socially? With ‘blight’ effectively still in the toolkit for the policymakers, designers, builders, and bankers who help shape urban regeneration, one wonders what lessons have been learned from our past.

2.

Blacks who moved north after the Civil War and into to the twentieth century faced significant challenges. As their population in northern cities grew from the migration, their segregation into identifiable neighborhoods became more defined. These neighborhoods quickly became overcrowded, underserved, and disinvested. During the Great Depression—and much like today—blacks were more affected by the depressed economy than whites.

3.

In response to these conditions, Dr. Benjamin Osborne began an organization called the Consumer Unit, acting on his mission to “lift [the Indianapolis Negro] out of the mire of economic serfdom to a point of economic stability by producing and marketing some of the necessities of life instead of remaining a dependent consumer factor.”[1] The organization was conceived as a large-scale cooperative that would produce and sell food.

4.

He asked for assistance from the federal Rural Resettlement Administration for his project. White landowners and organizations feared the project would be for predominantly black residents and successfully lobbied the federal government to not fund the project.[2] Instead, in 1935 the New Deal government approved and built Lockfield Gardens in Indianapolis, one of the first segregated public housing developments in the United States.[3]

5.

In researching my own family history, I stumbled upon reports about Flanner House, a social services organization in Indianapolis. The documents included photographs, budgets, and even building plans on the organization’s work transforming a slum in the inner city into a community with garden plots and newly constructed homes.[4] This story is compelling in that it narrates the historical decline and recovery cycles of the city, and the people therein.

6.

My grandfather was one of those people. Albert Allen Moore graduated from Tennessee State University in 1934 with a bachelor’s degree in Agriculture. Like many blacks escaping the Jim Crow South he moved northward for a better life. He came to Indianapolis where he eventually found work as the Agricultural Director for Flanner House. He taught other blacks from the Great Migration how to farm vacant lots within the city. His work, essentially what we today might call urban agriculture.

7.

During and after World War II people in the community experienced higher food prices, in part due to shortages in Europe.[5] Access to affordable and healthy food became a critical issue to the viability of the community. The cooperative model that Dr. Osborne first envisioned was later implemented at Flanner House in the early 1940s. With donated funds and land they began a comprehensive urban agriculture program as a part of a “Self-Help Services” unit.

8.

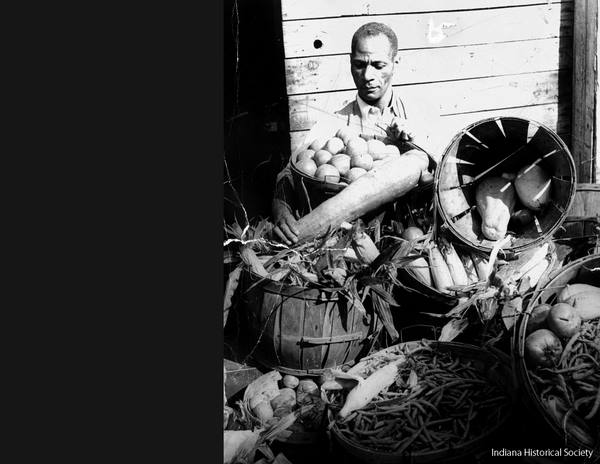

Through the Garden Program, families and individuals were offered plots of land and given access to tools, mechanical plowing, seed, canning facilities, and consultation with the Agricultural Director. The program grew over several years to include six hundred garden plots on nearly one hundred acres of urban land on the city’s near north side. Over two hundred families participated in the program.

9.

While the program focused on food and agriculture, economics and community foundations were always important considerations. Documents show that Moore also envisioned and directed these Self-Help programs as a social bridge to connect young people and seniors, men and women, those from the rural south, and those who grew up in the city and had never seen a farm.

10.

They also provided indoor training that focused on home economics, canning, food preparation, and nutrition. The community was affected by food-related ailments such as diabetes and heart disease. Home economics was taught to literally connect healthy food with physical and economic health.

11.

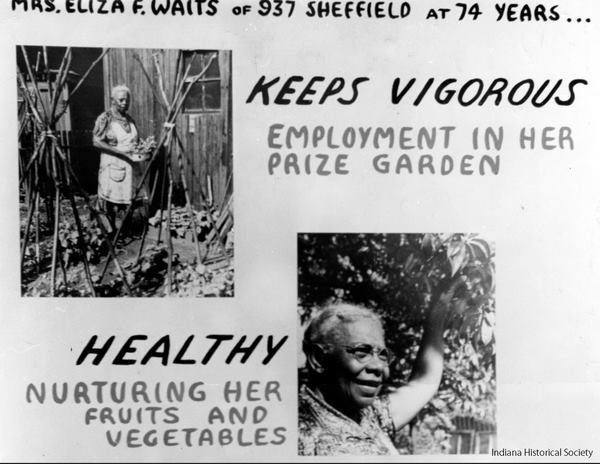

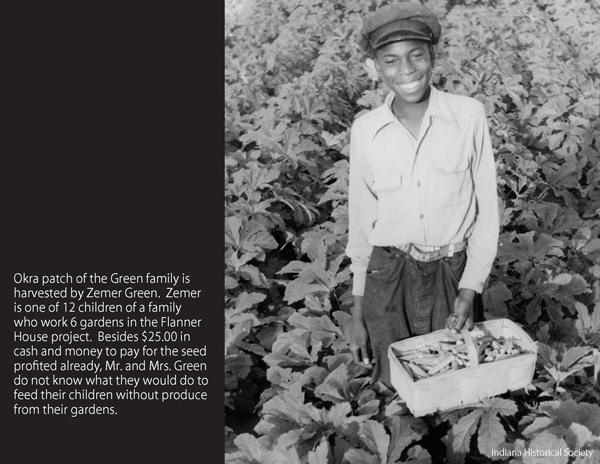

The gardens were especially encouraged as an activity for teenagers, mothers with young children, and seniors. These groups were not as able to get regular paying work; however, through the gardens, they were able to contribute to the sustenance of their families. Also, the program needed to be affordable, and had the promise to provide people with supplemental income. While some families cultivated land for food for their own households, others used multiple lots to generate extra produce to sell for additional income.

12.

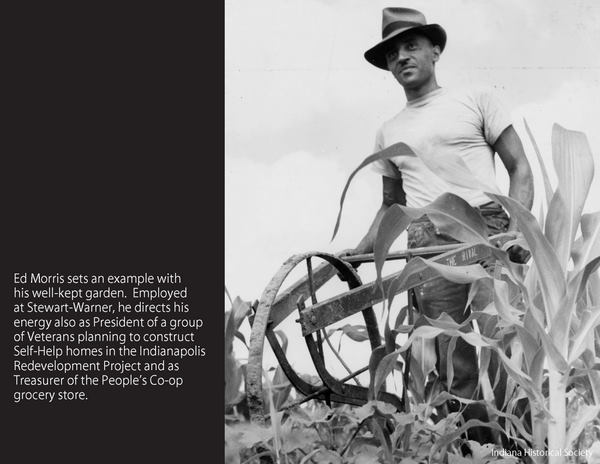

After WWII, the program included veterans in its programs under the GI Bill. By 1944, they had constructed a large cooperative building that included a larger cannery, community meeting spaces and classrooms, and a food market. Flanner House later opened a credit union; many Garden Program members would save money from selling their canned produce to start businesses, educate their children, and buy homes.

13.

With a group of only 21 low- to middle-income blacks, Flanner House initiated the Fall Creek Homes project, a large development near Downtown Indianapolis. The plan included over 300 residential units, open space, and even a watershed plan for Fall Creek. Many of the individuals who participated in the program worked in a variety of occupations from postal clerks and police officers, to workers in the automotive and pharmaceutical industries.

14.

The group got approval from the City Planning Commission in 1945 to acquire and plot a tract of land along the creek. The Commission, however, should not get much credit for this plan to improve the living conditions of the city’s growing black population as it is clear their agenda was to create a “place” for blacks to go so they would not move into the nearby established white neighborhoods.

15.

A fund was established, including a significant contribution from the city’s pharmaceutical magnate, Eli Lilly, Jr., to provide for the purchase of land, construction equipment and materials to build the homes.

16.

The premise of the program was simple—people would be trained in the skills needed to contribute to the construction of their own homes, thereby significantly reducing the costs of housing. After work and on weekends, the small group with no construction experience worked on a pilot home; it took them nearly 6,000 hours to complete.[6] It was a family affair.

17.

Once the homes were completed, they were purchased using FHA mortgages. The proceeds from the sales were directed back into the housing fund and other Flanner House programs serving the community. With lessons learned from the pilot home, and with individuals dividing tasks suited to their interests and abilities, the group was eventually able to construct the homes in just over 2,100 hours.

18.

The homes were designed by Hilyard Robinson, a prominent black architect known for his work with affordable housing. With significantly reduced labor costs, the homes were constructed for 40 percent less than what they would have cost using conventional housing development models.[7] Habitat for Humanity began using a similar self-help housing model twenty-five years after Flanner House completed their first home.

19.

The project was successful in creating one of the first black communities with homeownership in the city. It gained national acclaim, and eventually the model was exported to other contexts. They honed their program into an essentially corporate model, complete with branding, slogans, and endorsements.[8] They showed that there is the potential to be a pioneer in your own back yard, that it is possible to colonize your own neighborhood.

20.

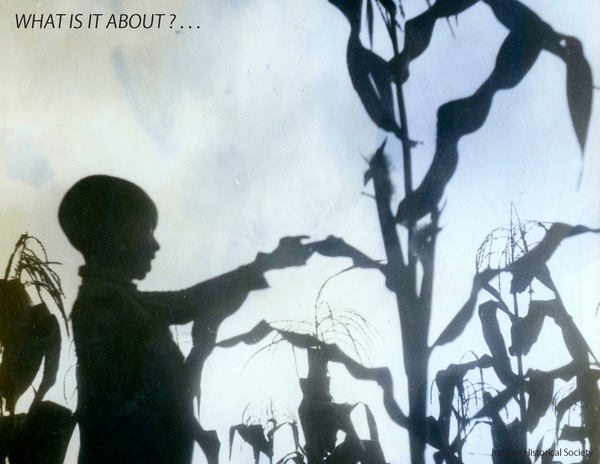

I will end with some propaganda from Flanner House’s “New Frontier” plan that I think is still an appropriate charge for us today; it states:

What is it about? About people. About their needs. Their abilities. The land the live on. The land they till. The food they grow. About the cities they live in. About the jobs they do. How they do them. And about the houses in which they live. About what people know. And don’t know. And what they ought to know. Ought to know how to help make America still greater.[9]

End Notes

Images: Indiana Historical Society

[1] Lou, Emma, and Lana Ruegamer. Indiana Blacks in the twentieth century. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000. p. 78.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Lockefield Garden Apartments Records, 1935–1954.” Indiana Historical Society. 5 February 2011. Web. http://www.indianahistory.org/library/manuscripts/collection_guides/m0786.html#HISTORICAL

[4] Indiana Historical Society

[5] “More Than 60 gardeners have registered for garden plot here,” Unknown newspaper article.

[6] Kimbrough, Joyce. “An Adventure in “Self Help” Building,” Indiana Historical Society. 5 February 2011. Web. http://images.indianahistory.org/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/dc018&CISOPTR=3438&REC=11

[7] Ibid.

[8] Fundamental Education.” Indiana Historical Society. 5 February 2011. Web. http://images.indianahistory.org/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/dc018&CISOPTR=4830&REC=19

[9] “Fundamental Education.” Indiana Historical Society. 5 February 2011. Web. http://images.indianahistory.org/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/dc018&CISOPTR=4830&REC=19

This is an awesome presentation. So glad you introduced me to this history, Joyce. Looking forward to working with you! DeShong

My father, Fred Page, Sr., is an original proud builder of Flanner House, still in his home on 13th St.

I even bought a home on Fall Creek and have been there long enough to pay for my home. So the article

was very interesting to me.

Hi Phyllis,

Sorry, it has taken so long to respond but it has been a busy time for us. I would love to talk to you and your Dad about his experiences with Flanner House. We have done a lot more research and are finding what amazing things were done at FH back in the day. And – I have good news about what is going on with us now. You can email us at info@urbanpatch.org and I will make arrangements for us to get together. I would love to hear your father’s (and your) story. There is an event that is coming up you would surely be interested in attending.

Hope to hear from you soon.